One of my favourite poets in the whole wide world is Polish!

I discovered the works of Nobel Lit Prize Winner Wisława Szymborska as a secondary school kid, back in the nineties – loved them so much; huge influence on me, etc. Unfortunately, her output wasn’t huge, so there wasn’t an extra tome of her works I could check out for this project. And I’d already used Czesław Miłosz - Poland’s other Nobel Lit laureate – for my Lithuania book.

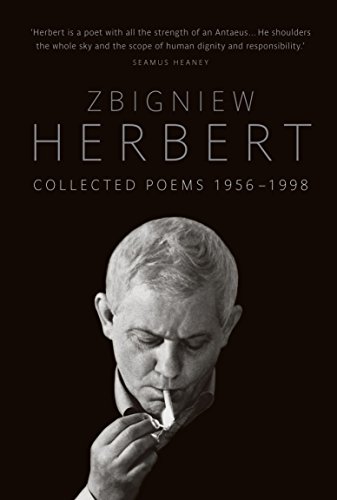

Fortunately, there are lots of famous Polish poets. Such as this guy:

I’d heard his name bantered about amongst my friends, so I

figured, yeah, why not read something of his? (Yeah, yeah, he was born in Lwow, which is now part of Ukraine, but it was Polish while he was a kid.)

This was the library’s only volume of his works – ye compleat edition, running to 571 pages. But mirabile dictu, it’s good. So good. (I’d considered abandoning it for Adam Zagajewski’s Eternal Enemies, a convenient, skinny little codex, but when I leafed through that, I found myself longing for the lambent voice of my man Herbert.)

This was the library’s only volume of his works – ye compleat edition, running to 571 pages. But mirabile dictu, it’s good. So good. (I’d considered abandoning it for Adam Zagajewski’s Eternal Enemies, a convenient, skinny little codex, but when I leafed through that, I found myself longing for the lambent voice of my man Herbert.)

We’ve nine different volumes of his poetry packed into this

tome:

Chord of Light (1956)

Hermes, Dog and Star (1957)

Sudy of the Object (1961)

Inscription (1969)

Mr Cogito (1974)

Report from a Besieged City (1983)

Elegy for the Departure (1990)

Rovigo (1992)

Epilogue to a Storm (1998)

So we get to follow this man from a post World War to a

post-Cold War era; from youth; from the age of 32 to 78. And over the five

decades we see his voice develop, shift from focus to focus, intensify and

mourn himself.

And it is the same voice throughout – a melancholy, erudite

voice, haunted both by the horrors of his own Communist (and pre-Communist)

society and the ghosts of classical history. He invokes Hermes, Apollo, Athena,

Marsyas, the Minotaur, Elektra, Claudius, Marcus Aurelius, Nefertiti – also

Mary Queen of Scots, George Orwell and the Emperor Meiji, come to think of it –

but not in a show-off-how-smart-I-am way, but to invoke archetypes of eternal

drama to show that the tyranny and torture of his land (of all lands) have ever

been thus.

Loads of specific references to his childhood and his Polish

contemporaries, too, which were a little harder to get. He calls himself Mr

Cogito (therefore he is?) in the latter half of his career, documenting what he

sees as his loserly life. But fundamentally, he’s engaged in the same Szymborska-esque

mission of mourning for the entire world, for the whole of history.

That hits me, you know? This is poetry that makes me want to

write more poetry. To join in the chorus as a testament. Gah.

(Though I personally do like Szymborska better still,

because she also finds joy in the senselessness of the universe. But it’s not a

competition. Is it?)

Representative quote:

I probably like his prose poems best, but this piece spoke of nation in a way that resonates a lot with me.

TAIL OF A NAIL

For lack of a nail the kingdom fell

- our nannies’ wisdom teaches us – but in our kingdom

there haven’t been nails for a long time nor will there be

neither those handy little ones used for hanging pictures

on a wall nor the big ones with which coffins are sealed

but in spite of this and perhaps precisely because of it

the kingdom endures and even gains others’ admiration

how is it possible to live without nails paper and string

bricks oxygen freedom and whatever else you like

evidently it is possible because it endures and endures

people in this country live in houses and not in caves

factories smoke in the steppe trains cross the tundra

and on the cold ocean a ship blows its bleating horn

there is an army and police a seal an anthem a flag

on the surface it’s just like the rest of the world

it is only on the surface because this kingdom of ours

is not a creation of nature or a creation of humanity

seemingly enduring built on the bones of mammoths

in reality it is weak as if suspended between

the act and the thought existence and nonexistence

a leaf and a stone fall so do all things real

but ghosts live a long time stubbornly despite

sunrise and sunset revolutions of celestial bodies

on the disgraced earth tears and things fall

Next book: Uladzimir Karatkevich's "King Stakh's Wild Hunt", from Belarus? Or Vladimir Kozlov's "Number Ten: A Novella In Translation"? Not sure yet.